What does the Mullins Effect mean and how to measure it?

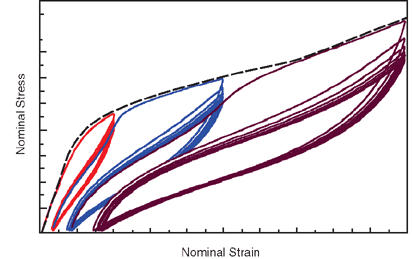

The Mullins effect is the stress-softening observed in rubber when it is loaded for the first time to a given strain. On subsequent loadings to the same strain, the rubber shows lower stress.

Once “damaged” by a prior stretch, the rubber never quite goes back to its original stiffness.

Image from: https://abaqus-docs.mit.edu/2017/English/SIMACAEMATRefMap/simamat-c-mullins.htm

What’s happening?

Unlike the Payne effect (filler network breakdown at small cyclic strains), the Mullins effect involves large deformations and changes inside the rubber matrix itself:

Key mechanisms include:

Breakage of weak polymer–filler bonds

Slippage or rearrangement of polymer chains

Micro-damage in the filler–rubber network

Possible chain scission at very high strains

After the first loading:

Some internal structure is permanently altered

Reloading follows a softer stress–strain path

The effect depends on the maximum strain previously experienced

How it appears experimentally

In a uniaxial tensile test:

First loading → high stress

Unloading → hysteresis (energy loss)

Reloading to same strain → lower stress curve

Loading beyond previous maximum strain → stiffness increases again until a new “damage level” is reached

This creates a characteristic stress–strain loop.

Key characteristics

Strain-history dependent

Partially irreversible

Occurs in filled and unfilled rubbers, but is much stronger in filled systems

Strongly tied to energy dissipation (hysteresis)

Why it matters in real applications

The Mullins effect impacts:

Dimensional stability

Fatigue life

Sealing performance

Load–deflection behavior

First-cycle vs in-service properties

Examples:

Rubber seals feel “softer” after initial installation

Tires experience property changes after first use

Vibration isolators shift stiffness after commissioning

Factors that influence the Mullins effect

Filler content and type

Quality of filler dispersion

Polymer–filler interaction strength

Maximum strain level

Temperature

Strain rate

Unlike the Payne effect, resting the material does not fully restore the original stiffness.

Mullins vs. Payne (side-by-side)

Feature | Mullins Effect | Payne Effect |

|---|---|---|

Strain level | Large | Small to moderate |

Loading type | Quasi-static or cyclic | Dynamic oscillatory |

Reversibility | Mostly irreversible | Largely reversible |

Main cause | Polymer/filler damage | Filler network breakdown |

Typical test | Tensile loading | DMA / RPA strain sweep |

Modeling the Mullins effect

Common approaches in constitutive models:

Damage mechanics models

Pseudo-elastic models (e.g., Ogden–Roxburgh model)

Energy-based softening formulations

These are essential in finite element analysis of rubber components.

Disclaimer

Please be aware that the content on our website is provided for general informational purposes only and should not be interpreted as binding or professional advice. The information presented here is not a replacement for tailored, legally binding advice suited to specific circumstances. Although we make every effort to ensure the information is accurate, up-to-date, and reliable, we cannot guarantee its completeness, accuracy, or timeliness for any particular use. We are not responsible for any damages or losses that may result from relying on the information provided on our website.